Perplexing Plague Cures

In every pandemic throughout history people have tried all sorts of things to protect themselves or cure themselves from illness. The current pandemic has been little different in that regard. But how did people in the days of the most notorious pandemic, the Black Death, seek to protect themselves? Daniel, our resident plague doctor, has been hard at work researching some downright bizarre cures for the Plague. He started by looking at the theories behind medieval ideas about health, hygiene and medicine…

Knowledge is Power?

Today, we know that disease is caused by microscopic organisms. Bacteria and viruses tend to be the primary culprits. However, it wasn’t established until 1861, thanks to the work of Louis Pasteur and followed up by Robert Koch. Until then, doctors of days past had to rely on other theories for what caused sickness.

In the initial outbreak of the Black Death, the primary one was the four humours. This was based on the findings of the Ancient Greeks, who were highly revered even after their time. They held that the body was comprised of four elements (the number four was something of a special one for the Greeks). These were:

· Blood

· Phlegm (snot)

· Yellow bile (stomach acid)

· Black bile

Humourism held that these four elements existed in balance in the body. If there was an excess or a deficiency of any one of them, the imbalance would result in sickness. For example, a fever could be seen as an excess of blood and a cold was due to an excess of phlegm (so much so that it comes pouring out of your nose!). Treatments revolved around restoring this balance.

Another popular one was miasma theory: the presence of bad air which spread sickness. In fact, the 1349-1351 outbreak was believed to be caused by a bad air which resulted from a conjunction of the planets boiling the seas and producing the vapour (movement of the planets held an important role too). Thus the best well to counter it was to dispel the bad air or else try to avoid breathing it.

Religion also played an important role. People were far more pious in the Middle Ages and the Church held a lot of power. Nothing like the Black Death had ever been experienced before, so many believed it was divine punishment from God for some great societal or personal sin. Hence, some turned to the Almighty in the hopes He might lift their sickness from them.

With all that established, let’s take a look at some of these cures!

Appealing to the Lord

If the Plague is punishment from God, the best thing to do is seek His forgiveness. As such, individual or collective prayer was practiced in earnest. Church bells were also believed to hold some power, being used to drive away demons and disease with their ringing. However, one movement that truly stands out is one that occurred in Germany. With the increased death and the Church seeming powerless to prevent, there were calls for some kind of reform. It was found in the Flagellants.

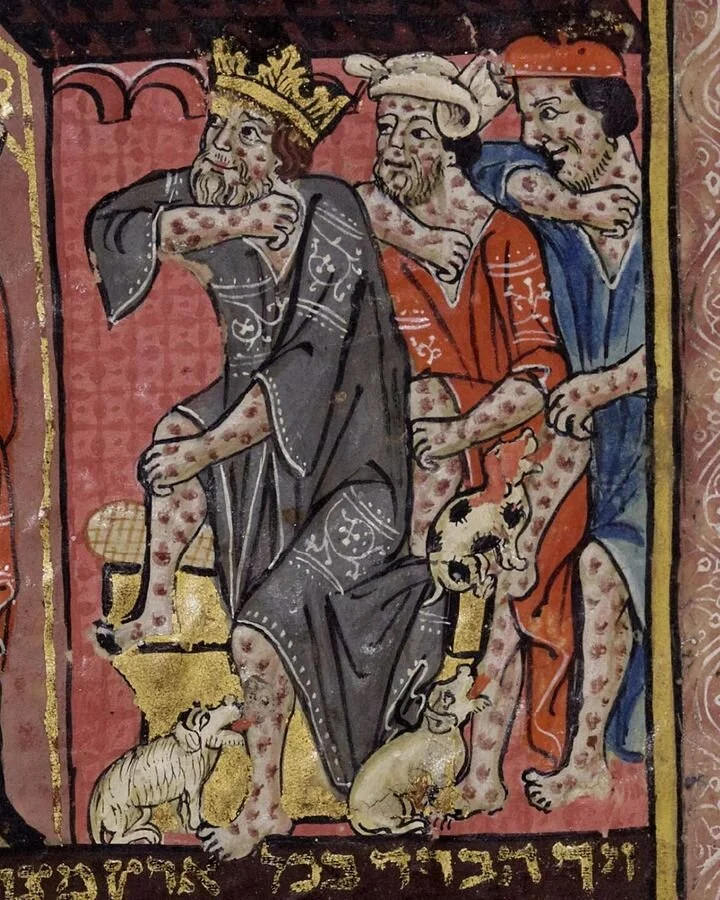

Philip Ziegler writes about them in detail in his book, ‘The Black Death’. Unlike the Church, who placed power and importance in the priests and sung in impenetrable Latin, the Brotherhood of the Flagellants placed the power of salvation in the hands of the people and spoke the common language. They numbered 200-300 strong at their peak and rather than simply praying, they offered an actively physical way to ask forgiveness of sin. With their faces covered by hoods, their backs exposed and their bodies decorated with crosses, they would gather in the centre of towns and cities. Then, they would make a public display of beating themselves with scourges and whips while chanting hymns and please to God.

Their primary belief derived from the understanding that if God was punishing them for sin, then the act of physical suffering would alleviate others and themselves of the Plague. In truth, not only did they make an unnecessarily public, painful example of themselves but they likely served as another way for the Plague to spread. Bandits would also tack on to their processions and attack the towns they visited, so they didn’t stay popular for very long.

Clear the air!

To ward away the miasma, a few different methods were recommended. In the outbreak of 1349-1351, it was believed that the foul winds that carried the Plague had risen from oceans in the south. So all people had to do was close any windows facing south and open any north facing windows to let in the purer air. Even better, just don’t live anywhere south or near the sea and get away from the source of the infection if possible.

There were also ways to purify your home or local area. Doctors would advise against strenuous exercise, since it could open the pores of your skin and render you vulnerable to miasma. Public health measures called for large fires to be burned in the streets. These could be of scented woods like juniper, ash, oak and pine or large barrels of tar to cleanse the air. Keith Wrightson, in Newcastle’s outbreak in 1636, notes the use of the latter.

Oddly, the people thought to be safest were those who cleaned latrines and toilets. According contemporary John Colle, the best antidote to bad air was more bad air and those who worked in these professions were to be ‘considered immune’. The outbreak in London in 1665 had their own peculiar ways of cleaning the air. The smoking of tobacco was recommended to all, even children. Likewise, gunpowder was another effective purifier, resulting in regular firing of guns and cannons to disperse it into the air.

Restoring balance

To bring balance to the humours, doctors would practice ways to remove the excess. The most common practice was bloodletting. This was carried out by general, barber surgeons who performed such practices, along with cutting hair and pulling teeth. They would use the cloth applied after bleeding to tie on poles outside their businesses to show how successful they were. This is the origin of the red and white striped pole barbers still use today!

Bloodletting itself, the act of cutting a vein to drain away blood, would be determined by the location of the bubo (large swellings) that were a symptom of the plague. For example, if the bubo was near the head or neck, the doctor would cut the celaphic vein between the thumbs. If it was under the arm, the pulmonary vein around the middle or ring finger was severed. It was important not to cut the wrong vein, or good blood would be wasted and bad blood would take its place. Practices varied, but at least one recommends bleeding until the patient passes out. Leeches were also a way to drain bad or excess blood from the body, usually applied to the location of sores and swellings.

Bloodletting and leeches weren’t the only ways to balance the humours. John Kelly, in his book ‘The Great Mortality’, shows that lifestyle changes could also play a part, since physicians found that both mood and diet were factors in guarding against disease. Along with not partaking in strenuous activity, some practiced living in moderation (limiting company and sampling only fine wines and food) or excess (drinking themselves stupid in taverns and gorging on food) to ward away Plague. Certain food was advised against, though the advice was perplexing and contradictory. Fruits and vegetables were a particular sticking point, with one doctor recommending lettuce while Paris medical experts forbade it. Wise to avoid were foods which spoiled easily like milk, meat and fish (especially if it was infected with bad air from the sea!).

Moods and feelings were also seen to influence the severity of disease. Positive feelings strengthened one’s disposition, while negative feelings worsened it, known by Paris medical experts as an ‘accident of the soul’. Especially to be avoided was weeping, speaking badly of others, worry, fear and wrath.

Take this and call me in the morning

Naturally, there were things doctors would recommend their patients take to rid themselves of Plague. Soothing potions of all kinds were prescribed, commonly those with rose water and vinegar (known today as actual antiseptics). Another, more expensive option was theriac (or treacle), based on another Ancient Greek practice. Comprised of over 70 ingredients including honey and opium, then left to age for ten years, it was a believed cure-all for virtually anything, from dog and snake bites, to poison and disease.

Powdered minerals were also recommended, giving hints to something akin to witchcraft. Gentile of Foilgno swore by emerald drunk with wine, so potent that a toad’s eyes would crack if they looked at it. Gold was also believed to be a natural purifier, imbued with the power of the sun and soaked in substances like rose water to drink afterward. Some even peddled ‘miracle’ cures such as unicorn horn and bezoar stones (taken from goat stomachs and believed to cure all known poisons).

Another measure was use of a poultice, something worn on a part of the body and used to draw out the disease. An onion was a common one, along with a dried toad, usually worn around the neck but there were stranger ones. Poisons like mercury and arsenic were used in amulets, believed to draw ‘pestilential particles’ out of the patient’s body. One Dutch physician advised taking the skull of an executed man, making soap from it and mix it with lard, linseed oil, spices and two ounces of human blood. An Italian surgeon advised cutting open the bubo and covering the opening with a dog, pigeon or rooster which was cut open at the chest. Another amulet was paper inscribed with the word ‘abracadabra’, written as a triangle and used to ward away evil spirits that might bring the disease. Joseph Byrne details all of this in his book, ‘Daily Life During the Black Death.’

The most bizarre was one recommended by the Royal College of Physicians in London, printed in 1636 as part of a general order to help guard against Plague. If somebody catches Plague, then they are to take a chicken, shave its bottom of feathers and press it to the bubo. The disease would be drawn out of the body and into the chicken. After the chicken dies, repeat the process until the chickens stop dying and you’re cured!

Now, we might laugh and scoff at these ridiculous measures. But it’s important to remember that the Coronavirus pandemic brought its own elements of strangeness. Toilet paper vanishing from the shelves. Conspiracies surrounding 5G towers. Doubt over the effectiveness of face masks. We even have those who peddle certain substances as cures or ways to ward off the virus. Everything from eating fruit that looks like the virus, to miracle mineral solutions, to a good old fashioned banana.

Perhaps, looking back on all of this, it doesn’t seem quite as bizarre now.