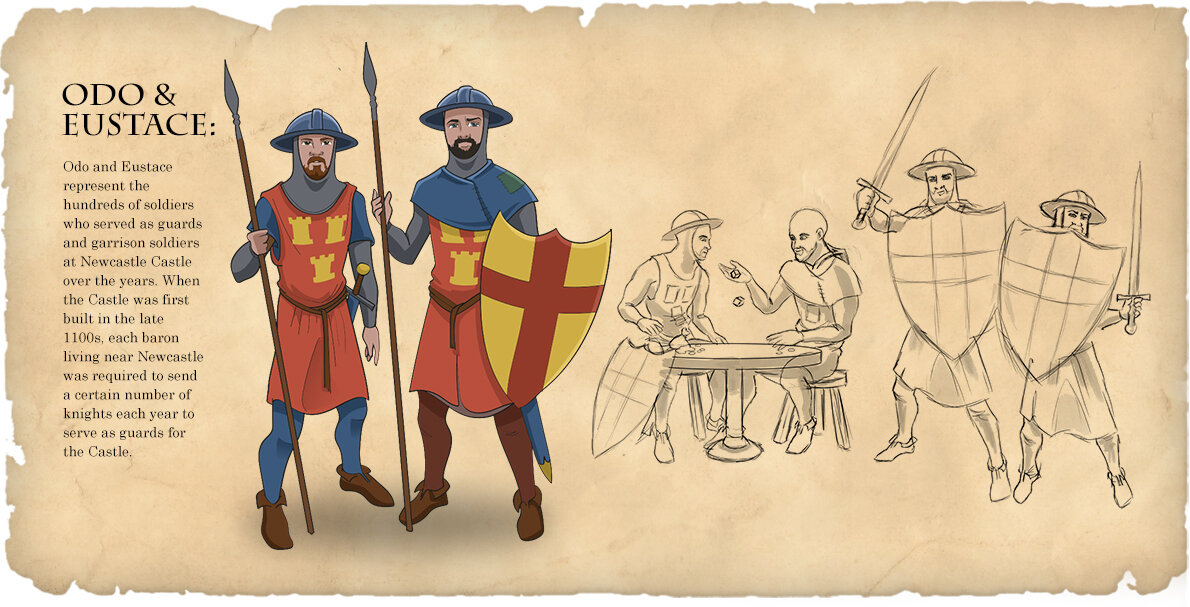

Castle Characters - Odo and Eustace

For many of us, the idea of castle garrisons go had in hand with the core functions and purposes of castles. For many, castles always had large garrisons of troops and their lives were ones of constant bloodshed because of the constant threat of warfare in medieval England (especially up here on the border with Scotland). In today’s blog, one member of our Castle Team, Corey Lyddon-Hayes, has been looking at the lives of two of our Castle Characters - Odo and Eustace, the Castle Guards.

Odo and Eustace, two (not so) gentlemen from our Castle Characters represent the host of colourful folk who served in the castle garrison here at Newcastle Castle. In this post, Corey will explore the background of castle garrisons, their composition, their role and purpose and their decline.

Background

The first question to ask is why were castle garrisons needed? Now, for most of us, this seems like a silly question, but the answer gives us an essential glimpse into the political and social environment of medieval England.

Sketch of the possible appearance of the Norman timber castle of Newcastle. By John Nolan

This leads us to one of the first instances of castles being built in England – the Norman Conquest of 1066. After the Normans had done the easy work of conquering a nation, the hard part was keeping that conquest. The Normans in England were a group about as large as a poor turnout to a football match and when compared to the 2-2.5 million strong population of angry Anglo-Saxons in England, their position does seem somewhat precarious. Proof of this comes in the form of the murder of Bishop Walcher in 1080, when a mob of slightly disgruntled Anglo-Saxons murdered the bishop and a whole church full of Norman nobles at St Mary’s church in Gateshead. In order to make up for this disadvantage the Normans had an ace up their sleeve – Motte and Bailey castles. By building castles, the Normans could centralise authority, protect themselves from their new, angry neighbours and show that they are in charge by being in a strong position with lots of soldiers. This helped what was a very vulnerable ruling group of Normans plant their roots to form the main body of the English nobility.

Now, we move further in time from those vulnerable early days of early Norman rule in the late 11th century to the 14th century Anglo-Scottish border. Here the importance of castle garrisons changed substantially, as the fourteenth century along the border with Scotland is characterised by an almost endless war between the two nations. The garrisons in this region became less focused upon protection from the local unrest and rivalry between local landholders to protection against invasion. The invasion of Scotland by Edward I – known as the ‘Hammer of the Scots’ – was not too effective but was not a complete disaster (and earned Edward his first acting role as the main villain in the 1995 film Braveheart) . It was under his son Edward II that control was lost, the English army was swept aside at Bannockburn (1314) and the Scots were in the ascendancy over England giving them a free hand in the north. It is around this time that castle garrisons in the north were (reasonably) bolstered.

The soldiers of a castle garrison were essential ‘staff’ within a castle because without them, a castle loses all defensive and authoritative power – they make the castle! Now, this has been a very quick view of why castle garrisons were needed, but I think it has spoken volumes. Garrisons were employed in order to both protect their lord from internal and external threats and these changed drastically through the medieval period, from being used to protect a foreign conqueror from their subjects to protecting a kingdom from its enemies.

Who were the garrison?

Our next big question is directed towards understanding castle garrisons, and looking into what made up a castle garrison? For this, we will query how many soldiers served in the garrison, who was in charge and what types of soldiers were there.

The castle garrisons in the north east of England greatly vary, with exposed castles in areas of immediate threat usually housing more troops. The garrison of Newcastle upon Tyne had 70 men in 1323 (when the threat of Scottish incursions was very real), owing to the fact that Newcastle Castle was surrounded by a heavily defended town with defenders of its own (Cornell, 2006: 9). David Cornell, in his brilliant PhD thesis English castle garrisons in the Anglo-Scottish wars of the fourteenth century, outlines the garrison at Newcastle, which had one knight in command, nine men at arms and 60 hobelars (we’ll come on to them in a moment). Garrison numbers did decline in times of peace or low risk as the maintenance of a garrison was very costly for the crown.

Newcastle castle had one knight in residence as part, and leader, of the garrison in 1323. Two knights are highlighted in this period as being Sheriff of Northumberland and Constable of the castle one after the other – John de Lillburne (until 1328) and Roger Mauduit (until 1334). Both knights served in succession as constables and sheriffs at Newcastle, meaning that they will have been in charge of our garrison. We can expect all of the similar training, weapons and armour as our knight Sir Aymer de Atholl – so be sure to check out our blog post if you haven’t!

Men at arms and common footsoldiers in combat, from the Holkham Bible. Image courtesy of the British Library, add ms 47682 f.40

Castle garrisons would house a group of soldiers known as men-at-arms who, on the face of it, look similar to knights and had much of the same equipment but lacked the knighthood and nobility. These were soldiers experienced with most weaponry being able to use a broad range from swords, spears and other polearms to crossbows – and this experience likely made them very expensive. These chaps would have worn the most fashionable medieval helmet going at the time – the kettle helm – named because it looked like a medieval cooking pot but was very well designed to protect soldiers from projectiles and other attacks (British soldiers in WWI wore a similar style helmet). Men-at-arms traditionally formed the mainstay of castle defenders, but in the fourteenth century, new troop types started to replace them.

Now, we come on to the new and shiny troops putting the roles of our hard working (mostly!) men-at-arms at risk. Our old pals Odo and Eustace represent some of these new, shiny soldiers called hobelars. Hobelars were light cavalry, which at first glance could be mistaken for mounted knights – they wear some armour and a kettle helmet, carry a sword and a lance. As the period developed, mounted archers also started to become popular. The benefit of these troops over men-at-arms is that they are fast thanks to their horses and can quickly move about not only to attack any enemies but also to provide support to nearby castles or places under attack. So, Odo and Eustace were a new form of garrison soldier which went on to overtake men-at-arms as the mainstay of garrisons throughout the remainder of the period. So, luckily for Odo and Eustace, the hobelars enjoyed a degree of job security!

The traditional background of a castle garrison was born out of a need for defence – they were there to make sure that no one nicked their boss’ castle, which was likely to have been their home too! Now, I want to analyse the effectiveness of castle garrisons in this role.

We get a good impression of the types of people who made up the ranks of a castle garrison. People like Odo and Eustace would have been hardened veterans and were certainly not the kind of person you would want to get on the wrong side of! For men like Odo and Eustace. getting a gig as a man-at-arms or hobelar in a castle garrison looks to be rather nice; you aren’t at a great deal of risk, you get paid and if you don’t you’re legally allowed to take something known as victuals – essentially nicking things like food and beer from the local people to sustain yourself. For all of the perks of the job, you are still a soldier (probably a very good one) and you are expected to fight should you be required, potentially having to hold out during a siege or venture out from the safety of the castle to fight.

If they were unlucky, Odo and Eustace might have had to protect a castle during a siege. This will have been an awful experience for the garrison as the attackers try to take control of the castle from a handful of men.

Normally, the besiegers (attackers) will have waited outside, blocking the garrison in and waiting until the defenders were forced to surrender from starvation, thirst or losses (and no small amount of boredom)! Many castles had enough food, water and provisions to last up to one year.

Medieval depiction of a siege. Image courtesy of the British Library, Royal MS 16 g vi, f7v

The besiegers would normally launch attacks with ladders and siege towers trying to get soldiers on the walls, men trying to batter down the gate with a battering ram all the while siege engines like the mighty trebuchet hurled giant stones at the castle. A siege would have been a horrible event and we can only imagine what a soldier of the garrison will have went through, especially considering the fear of being killed in the fighting and possibly being executed should the enemy win.

Alongside the harrowing expectation to defend a castle during a siege, garrisons were primarily expected to perform military actions alongside defending the castle. Enemy armies could easily bypass castles and the men of the garrison would venture out from behind their walls to harass the enemy supply lines, skirmish with the enemy and still exercise control of the surrounding landscape.

If the castle garrison ‘sallied out’ (left the castle to skirmish with the enemy to you and I) we can be certain that this would be a brutal, bloody affair. It is for this reason that castle garrisons and their leaders, known as constables, had to be experienced and well drilled – knowing exactly what to do and sometimes acting on their own initiative, whilst being hardened and experienced enough to withstand the sheer terror of medieval combat at its most gruesome.

For all of the benefits of a castle garrison men like Odo and Eustace were a dying breed. With the advent of gunpowder weapons such as cannons and changes in military tactics, the importance of castles in warfare dwindled and the need for garrisons along with them. Castles and their garrisons clung on through the remaining medieval period but the damage was irreparable and the importance of castle and the soldiers within would only occasionally rear their heads during major conflicts such as the English Civil War.

Even though castles eventually lost their military role and the garrisons were replaced, we at Newcastle Castle still have a group a guards watching for potential Scottish invasion and generally avoiding patrols out in the cold. If you see any men-at-arms or knights on your visit to Newcastle Castle feel free to say hello!

Corey Lyddon-Hayes