Castle Characters - Sir Aymer De Atholl

Castle Characters

Over the last couple of months, you may have noticed some new and unfamiliar faces popping up in safety videos and on Newcastle Castle’s website. You’ll be seeing a lot more of them over the coming months as well, as they’re part of a project we’re calling ‘Castle Characters’. The idea is to help bring the past to life at Newcastle Castle by introducing you to some of the people you might have met if you’d been hanging around the Castle centuries ago. It can often be hard to imagine what day to day life was like in the past for ordinary people, and we hope that by meeting and learning about these characters that you’ll get a bit of insight into the kind of people who lived, worked and died here all those years ago. When choosing the characters for this project, it was important to us that these people wouldn’t be Kings or Queens of England, or anyone that grand. Some of them may have had titles, held land and been wealthy, but they are all more obscure figures from the town’s past. In short, they are (or rather they were) the people of Newcastle. Because we don’t usually have complete biographies from so long ago, we’ve had to piece together what we know of them from small mentions, and from other sources of information about their status or profession in the times when they lived. With some work, we can give a fascinating window into Newcastle in centuries long past.

Knight Life

The first of our Castle Characters is Sir Aymer de Atholl, and he is a knight. Knights are one of the iconic figures of the medieval period, and often one of the first things that people bring up when they’re talking about Castles. Everyone has an image of a knight, a dashing figure on a huge horse wearing shining armour, like Sir Lancelot from the stories of King Arthur. Those stories would all have been well known to Sir Aymer – he lived in the 1300s when King Arthur was the most popular ‘media franchise’ going, with poets and writers all over Europe churning out stories about chivalry, honour and adventure. But just how accurate is this image of a knight? Did they really ride round fighting dragons (spoiler, no) and rescuing maidens from towers (well, sometimes, but more on that in a later blog post)? And if not, what was their life really like?

Well, in this post we’re going to piece together the life of Sir Aymer de Atholl, a real knight who lived through the Black Death and the wars between England and Scotland; who survived siege and imprisonment; served as a soldier, judge and tax man; married and raised a family, and lived to a ripe old age.

The Game of Thrones

The first thing you might notice about Sir Aymer de Atholl is that fancy name. That gives away that we’re dealing with someone of importance. Most knights and nobles in medieval times were known as “de-something or other”. Robert de Clifford, Giles de Argentan, Henry de Bohun and so on. This is just French for “of”, and the place mentioned afterwards was usually their most important ‘manor’ or estate. The fact it’s in French tells you something to start with – the first language of the upper class in England was not English. This was a holdover from the Norman invasion, which is when most of these families first came to England. So where is Atholl? Well, Atholl is in Scotland, today it’s part of Perthshire but in the 1300s it was an important Earldom in Scotland, ruled from Blair Castle by the Earls of Atholl. There were plenty of Norman families holding land in Scotland by the 1100s as well as England.

The story of how a son of the Earl of Atholl came to be an English knight is worthy of Game of Thrones. In the late 1200s, Scotland was in serious trouble – the Queen (who was only 7 years old!) had died with no heir to succeed to the throne, and King Edward I of England was making moves to bring Scotland under his control. That he was known in his own time as “The Hammer of the Scots” should tell you something about how peacefully he attempted this. He first tried having a loyal puppet, John Balliol, put on the throne. But when Balliol refused his commands, he had him removed from his throne and invaded Scotland with a huge army of conquest. But a pair of Scottish knights, Sir William Wallace and Sir Andrew de Moray, began a rebellion that defied King Edward for years. Eventually, a Scottish nobleman, Robert de Brus (better known as Robert the Bruce) claimed the throne of Scotland in 1306 and fought a long and gruelling war against the English that lasted until 1314. During this time, every noble who held land in Scotland had to pick a side – neutrality was not an option, but swapping sides wherever you saw an advantage definitely was.

Aymer’s father, David Earl of Atholl, submitted to the King of England in 1307 and served him on the borders and in Roxburgh until 1312 (all this despite the fact Edward of England had his dad executed for supporting Robert the Bruce the year before!) But then he changed sides and went over to Robert the Bruce, who made him Constable of Scotland. They then had some kind of falling out and in 1314, David was banished from Scotland, losing his land but keeping the “de Atholl” name as a reminder of the title and lands they sought to reclaim. David and his sons would become loyal knights serving the King of England and fighting against the Scots on the northern border. So where does that leave Aymer de Atholl? Well, he seems to have been born in England sometime after his father’s exile from Scotland. He was the second son, and while his family name might sound impressive, it came with little land or wealth. His older brother inherited the claim to the Earldom, and Aymer had to make a living as an ordinary “working knight” …

The Order of Knighthood

So what did it mean to be a knight exactly? How did you get to be one? The first thing to get out of the way is that knighthood was usually reserved for the children of the wealthy – not necessarily VERY wealthy, but a step above the peasants. Like most children in medieval times, the children of knights and nobles learned to be knights by going through a kind of apprenticeship. They would be sent to live with another family in their castle or manor house from around the age of 7. There they would serve as a page until about the age of 12, acting as a servant in the household. Many people imagine being a servant as quite a lowly occupation, but in medieval times serving a noble household was seen as a very honourable way for a child to spend their time, and many of the servants you would have seen in a castle or grand house would have come from wealthy families.

From the age of 12, these apprentice knights went to serve a ‘fully qualified’ knight as a squire. They would follow the knight around taking care of their horses, polishing their armour, sharpening their weapons, serving them at dinner and so on. In return they would be trained, not just in how to fight in battle, but also in dancing, poetry, music and what have you. By the 1300s they’d also learn to read and write and get a decent education in how to run a castle, farm or manor – the noble families of the middle ages were a lot like big corporations today, and managing their property was a complicated job.

By the time a squire was 21, they were usually considered old enough to be knighted. This was an elaborate ceremony where an older knight or lord ‘dubbed’ the squire by tapping them on the shoulders with their sword (among many other rituals like being dressed in white robes, having someone give you a gift of spurs and so on). It was also possible for lords and the King to make commoners into knights for some particularly great service, usually for courage in battle. One of the most famous Knights of the 1300s, Sir John Hawkwood, was only the son of a tailor from Bristol.

We don’t know exactly when Sir Aymer de Atholl was knighted, or even exactly when he was born, but the first time he appears in our records is in 1344, and he is already referred to as “Sir” – the mark of knighthood. He was almost certainly at least 21 by then, so he was probably born sometime before 1323. Upon being knighted, he would have adopted his own coat of arms that would be painted on his shield and embroidered on the surcoat he wore over his armour to identify him. He bore the black and yellow striped shield of his family with the addition of a leopard to mark him out from his older brother.

Knight of the Shire

Knights usually owned land in the form of a manor – a posh house (not quite a castle) with a village or even a few villages nearby, whose peasants owed rent to the knight. Sir Aymer was paid rent by the people of Mitford, near Morpeth. This rent was supposed to give the knight enough money to maintain a horse and a good set of armour and weapons to serve the King when he called them up for his army (the usual Latin word for a knight, militis, just means soldier). But in the 1300s, Knights increasingly had a lot of other work to do on behalf of the King and his government as well as fighting in battles.

This is where we start to see Sir Aymer turn up in the records. In 1344, he was put in charge of the soldiers of Tynedale for the wars with Scotland, and in 1345 was the Commissioner of Array. This meant he had to make sure that the people of Tynedale were ready for battle, check their equipment and make sure the militia was properly trained and ready to deal with a Scottish invasion - quite a job for someone in their 20s! He was probably involved, along with almost all the other knights of the area, in the great battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346 where the Scottish army was defeated, and King David of Scotland captured. In 1347 he was serving in the lowlands of Scotland, and was the Sheriff of Dumfries, in charge of keeping Scottish prisoners and doing active military service. Not long after this, in 1349 and 1350 the Black Death ripped through England and Scotland, devastating the population – in County Durham, 50% of the population was killed. The wars with Scotland understandably went quiet for a while.

It was not just military service that knights were expected to do though. Aymer was also appointed by Queen Phillipa as a Justice of Assize, a judge hearing criminal cases in Northumberland. These would have been heard at the Castle, which was also the site of the gaol – the notorious dungeon known as the Heron Pit. In 1364 he was charged with capturing and imprisoning a gang of murderers who had done away with another famous local knight, Sir John Coupland. Later in his life, in 1381 he served as the Sheriff of Northumberland and Knight of the Shire (MP). The Sheriff was also usually the keeper of Newcastle Castle, so while serving in this job Sir Aymer would have overseen the Castle and all its staff. Being Sheriff was a thankless job, a combination of chief of police and tax collector, we have records of Sir Aymer complaining to the King that Northumberland had been so ‘wasted’ by Scottish raids that collecting any taxes was impossible!

He was probably a bit past active military service by this time, he was probably about 60, but had grown into a respected member of the local ‘gentry’. All this means that there is a surprising amount of mentions of Sir Aymer scattered around in different documents, most of it to do with financial transactions, arguments over bits of land or inheritances and so on. That’s the part of being a knight you never read about in the stories – all the paperwork! It’s no wonder lots of knights employed clerks to do that bit for them, if they could afford it.

Family Life

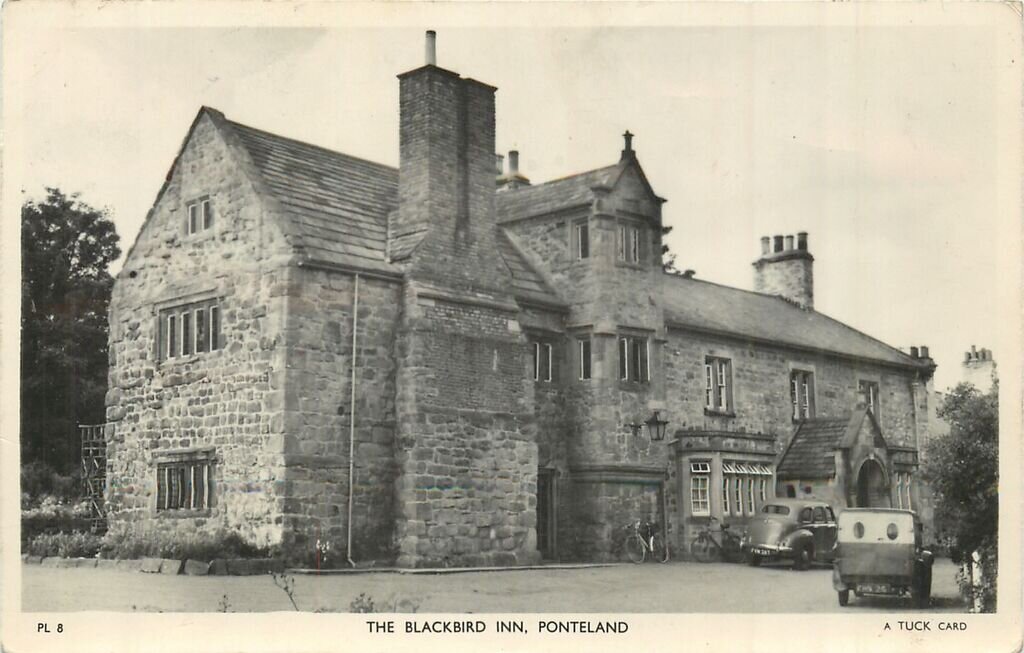

Sir Aymer was a family man as well as soldier, judge, policeman, politician, and tax collector. By the 1370s he had inherited or been granted quite a bit of land and lived with his wife Mary in his tower in Ponteland. This would have been a kind of fortified house, and part of it remains as the foundations of the Blackbird Inn. His family life was not entirely a happy one. He and his wife had a son and heir, also called Aymer (medieval families love to keep the same names, mainly to confuse historians), but he died before either of his parents. Our Sir Aymer also outlived his elder brother and his nephew, leaving him the last male heir of the de Atholl family. His wife died in 1387 and was buried in St Andrews Church, Newcastle where Sir Aymer dedicated a chapel, asking for people to pray for the soul of his wife and for him. He also had two daughters, who, while they could not inherit the family name, managed to find husbands among two of the other noble knights of Northumberland – Isabelle married Sir Ralph de Eure, and Maria to Sir Robert de Lisle (One of her descendants, Sir William de Lisle will make an appearance in a later post.) Their children bear their fathers names, and so it is with them that the name of de Atholl disappears out of history.

Otterburn

As if the death of his wife in 1387 wasn’t bad enough, in 1388 a massive Scottish invasion swept through Northern England and laid siege to Newcastle itself. The town was strongly defended by the legendary knight Sir Henry Percy, known as “Hotspur ” for his recklessness in battle. His recklessness would cost him dearly – when the Scots retreated from the walls of Newcastle he chased them down and engaged them in battle at Otterburn, a battle that would be disastrous for the English – Hotspur and his brother were both captured by the victorious Scots.

Sir Aymer must have thought he was a bit old for battle by this point – he cannot have been any younger than 65 and may have been a fair bit older than that! Sadly, he was not to escape. On their way north the Scots army stopped and briefly besieged his tower in Ponteland, destroying his home and burning the village. Sir Aymer de Atholl was captured by the people he would once have called his countrymen and was taken north into Scotland. Fortunately for him, as a knight he was worth a considerable ransom, and was released after its payment – one of the perks of the job.

Life, Death and Remembrance

Sir Aymer de Atholl died in 1402. We don’t know how old he was exactly, but he cannot have been any younger than 79, an impressive age for the medieval period! It’s especially impressive when you consider he lived a life of active military service, fighting hand to hand in some of the bloodiest wars fought in the British Isles, and lived through the Black Death that wiped out between a third and a half of the population of Britain. He was buried next to his wife in St Andrews Church in Newcastle, and at one time had an impressive brass monument on top of his tomb, showing him in full armour lying next to his wife in her finest gown, with their coats of arms displayed next to them. Sadly, nothing now remains of this impressive piece of art but the feet! He may have left Newcastle another interesting legacy though. In 1666 a Yorkshire gentleman called John Stainsby visited Newcastle and left a little diary of his journey – in it he notes seeing the tomb of Sir Aymer in St Andrews Church, and he was told that it was Aymer who gave to the town a piece of land lying outside the walls to hold an annual fair, which he says is generally called the Town Moor.

So there you have it! The eventful life of a real knight, and not a dragon in sight. Sir Aymer is just one of our Castle Characters who we hope will help to illuminate the medieval past for you here at Newcastle Castle.